Questions and answers

We ask a lot of questions. How did the Universe come into being? Why is there Being at all? How should we live our lives and conduct ourselves? Is there an absolute morality, rules of conduct that would be good for all and all times? Is there anything beyond what we can see? What happens after we die?

But should those questions always have answers? It is one thing to ask, but why should all questions have answers? We desperately want to know, but there is no reason our craving should be satisfied.

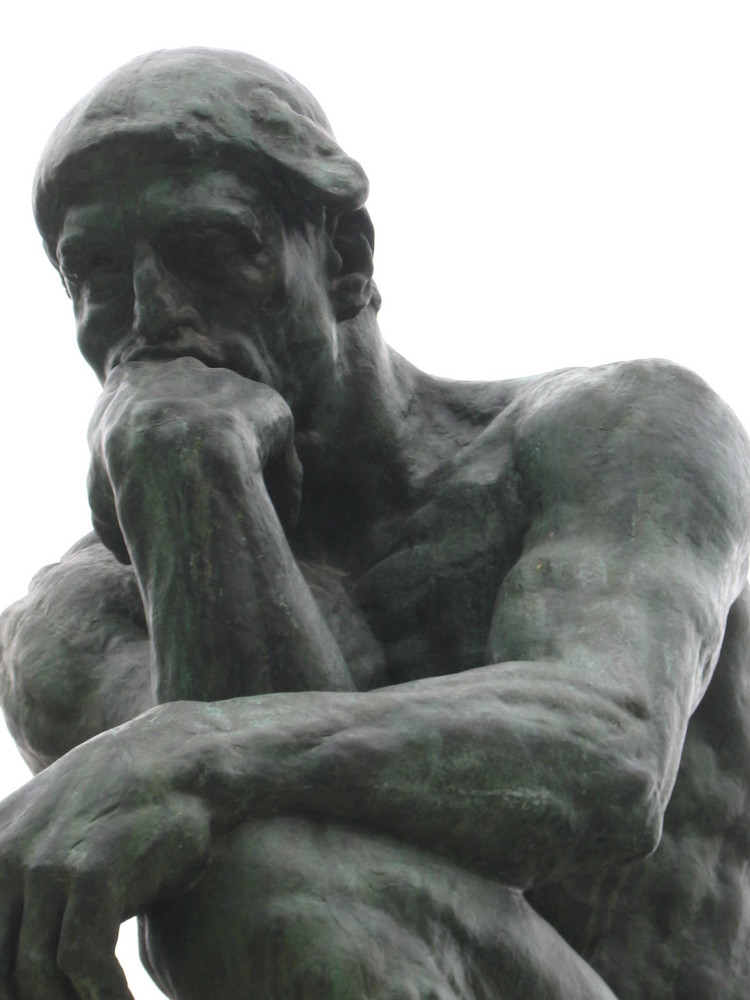

We can look for answers, and maybe that is what it means to be human: asking questions and looking for answers. This may be fruitful sometimes. For some questions about the workings of Nature, we have been able to find answers. For example, we have obtained a better understanding of how our body works and devised treatments and drugs that alleviate our miseries. We have been able to understand how electricity works and derived many comfortable benefits from this understanding. Useful answers have usually been found via rational thinking, observation, experimentation, confrontation of our ideas with reality, a continuous struggle to adjust our ideas to reality - and in limited contexts: asking how electricity works is a far cry from ultimate questions such as how the Universe came into being.

These larger questions have typically not yielded to rational thinking, and they may never be answered. Maybe we’ll figure them out one day. Or maybe they do not, in fact, have answers. Maybe our asking is clumsy and there is no answer to be had, or at least, not now.

Some of us are only too willing to make up arbitrary answers though, to concoct opiums of the mind to intoxicate themselves and others, because they can’t live without answers to all their questions (or because they want to manipulate and control others: fictions are a powerful political tool). In their childish psychology, they are entitled to always getting answers. But we should grow up and not delude ourselves, not lie to ourselves in our quest for answers. We should have the courage to acknowledge our limitations, our boundedness and inability to find answers to big questions. We should be honest and recognize when we do not know, and not become enmeshed with made-up answers to the point of mistaking those fictions with reality. Trying to create a reality that conforms to what we wish is not useful, nor healthy. We can choose to believe a story we like, for practical purposes, because it helps us in our lives, or just because we temporarily believe some story as a practical stopgap till we find a better explanation. But we should recognize that those stories are arbitrary constructions of our minds rather than reality, that they stem from our immature desire for answers, rather than accurately reflect what is out there. Some want to be demiurges, create reality, but our stories can’t be stronger than reality.

So, we should be honest, acknowledge our shortcomings in understanding the world, recognize that we are not necessarily entitled to get answers to all our questions, be courageous and not try to assuage our anxieties by conjuring up fake, alternate realities. And above all, we should not force others to accept our made-up stories. There is really no justification for that. Nobody has any right to assert their own stories as truer than anybody else’s. Your stories have no special preeminence over my stories, or my accepted lack thereof. I have a right to make my own stories as much as you do, or to not believe in any story if I choose to.